This article was originally published in my book “Brazil without stereotypes” in German in 2014.

The journey to the German-Brazilians began at the airport in Porto Alegre, the capital of the state of Rio Grande do Sul. North of this southern Brazilian metropolis lies one of the main areas of German immigration, which celebrated its 190th anniversary in 2014. Following Brazil's independence in 1822, Emperor Pedro I promoted settlement and agricultural use in several southern states in order to strengthen national unity. From 1824, emigrants were recruited in Germany and later also in Italy (see Curi, p. 24). It is difficult to come up with figures, but Kunath assumes that “regardless of whether or not they still speak a few words of German, today around five million are considered teuto-brasileiros” (Kunath, p. 34). The majority of German immigrants to southern Brazil came from the Hunsrück region, which can be generously interpreted geographically. The second large group of German immigrants were the Pomeranians, the majority of whose descendants live in the state of Santa Catarina. Most Brazilians of German descent live in Blumenau, where the second largest Oktoberfest in the world is celebrated. Unlike the Munich Oktoberfest, however, the Blumenau version is more recent. Founded in 1850 by pharmacist Hermann Blumenau, the city, which today has around 300,000 inhabitants, suffered severe damage after a flood in 1984. To get money into the municipal budget and to boost the morale, an Oktoberfest was celebrated for the first time in the same year. German roots and customs, as they are understood today, were not decisive.

The drive from the Porto Alegre airport towards Novo Hamburgo is anything but picturesque. Ugly industrial sites and suburbs are lined up next to busy highways. It takes quite a while to get out of the city. The next town, São Leopoldo, where there is a museum about German immigration, doesn't look any better from the highway, mainly factories and faceless districts. After about 35 km, I reach the first stop on my journey to learn more about German immigration, Novo Hamburgo, which has nothing in common with the Hanseatic city apart from the name. The name was chosen because most of the immigrants came to Brazil via Hamburg, but there were hardly any Hamburgers among them. Novo Hamburgo is not located on a major river, nor does it have a lousy first division team like its namesake. Novo Hamburgo is the “capital of the shoe”.

The boss of the shoes is Luis Lauermann, a mayor of German descent. To greet him, he first speaks a little Hunsrückisch, but then switches to Portuguese, not only because it is easier for him, but also because other employees of the city administration are present. “My father only really learned Portuguese in the military. I hardly knew any Portuguese either, until I started school. But it's different in the younger generation, where Portuguese dominates.” Like former Brazilian President Lula, Lauermann comes from the trade union movement. In 1990, he visited Germany at the invitation of the DGB. He was also in Trier, which was important for a Marxist like him. After that, Lauermann was no longer in Germany.

In Lauermann's opinion, origin no longer plays a role in local politics today: “This is a positive development, citizens vote according to political preference and not ethnicity. The biggest attacks against me before the election were that I am not from Novo Hamburgo, but from the nearby small town of Ivoti.”

After the meeting in the city administration, a largely unheated high-rise building, which is why most of the employees keep their coats on when it is around 12 degrees outside in June, we moved on to Felipe Kuhn Braun, who despite his young age, not yet 30, has already published ten books on German immigration in and around Novo Hamburgo.

Kuhn began researching German immigration to southern Brazil after inheriting a box of around 50 old photos from his grandmother. “The problem was identifying the people in the photos. So I started asking questions, first within the family, then to related families and so on.” Kuhn then wrote a book about his family. “I'm very interested in genealogy,” he explains in his living room. He later delved into the histories of other families and communities, such as Linha Nova. It helped that someone introduced him to the local community. “If you just knock on the door, it usually doesn't work. But if you convince just one person of your research, then it continues like a snowball system.”

In real life, Kuhn works in the press department of the regional parliament of Porto Alegre, “you can't make a living from books.” In 2007, he also visited Germany, especially the Teuto-Brazilians' home region, the Hunsrück, the Saarland and the surrounding area. But he has also been to Argentina and Paraguay, where some of the Hunsrückers moved when things weren't going well economically in Brazil.

Kuhn no longer learned German with his family, but attended courses at university. He complains that German is hardly spoken any more, especially in Novo Hamburgo, and that few people are interested in the history of the immigrants. The most difficult part of this history were the last years of the Second World War. Especially after Brazil declared war on the Axis powers (Germany, Japan) in August 1942, there were demonstrations and attacks on businesses that looked German, Italian or Japanese (see Kunath, p. 45). Glüsing gives examples from Rio where “German restaurants, clubs and other institutions had to change their names. The Bar Adolf became the Bar Brasil. Germans were not allowed to settle on the coast for strategic military reasons, and many were arrested as spies” (Glüsing, p. 28).

Kuhn was only able to prove the support for the NSDAP among the German-Brazilians around Novo Hamburgo with two photos of Nazi events: “After the war, understandably, nobody wanted to be associated with it. People don't exactly talk openly about that time.” For Kuhn, those still born in Germany were particularly receptive to National Socialism, whereas Brazilian Germans were much less so. It was not a big issue, especially in the countryside.

This is consistent with the figures on NSDAP membership in Brazil. Kunath puts this at 2822 members (Kunath, p. 48). At that time, there were still around 100,000 people born in Germany living in Brazil alongside significantly more German-Brazilians. Out of a total of 400,000 people, that would have been less than one percent NSDAP members. On the other hand, according to historian René E. Gertz, “there is not much opposition to be found either. The Nazis, who initially strolled through the streets with swastika flags and uniforms, were probably not held in particularly high esteem, but encountered little resistance when they took over the German associations” (quoted in Kunath, p. 53).

According to the historian Gertz, the position of people of German origin within Brazilian society only normalized in the 1970s, during the military dictatorship of all times. In 1974, General Ernesto Geisel, a Protestant of German descent, took office as president, and “this also made German-Brazilians respectable again” (Kunath, p. 60). But the pressure exerted on the Teuto-Brazilians during the world wars meant that their mother tongue also suffered greatly. Until the beginning of the Second World War, most Germans in southern Brazil lived in the countryside. In modern terms, these were parallel worlds in which little Portuguese was spoken and traditions were maintained. The German spoken in the German islands became increasingly independent from the Hunsrückisch spoken in Germany and also adopted Portuguese words and grammatical forms. In addition, around half of this parallel German world was Lutheran, which at the time was as exotic as Brazilian Muslims are today. In the first official census in 1872, 99.7 percent of the population described themselves as Catholic.

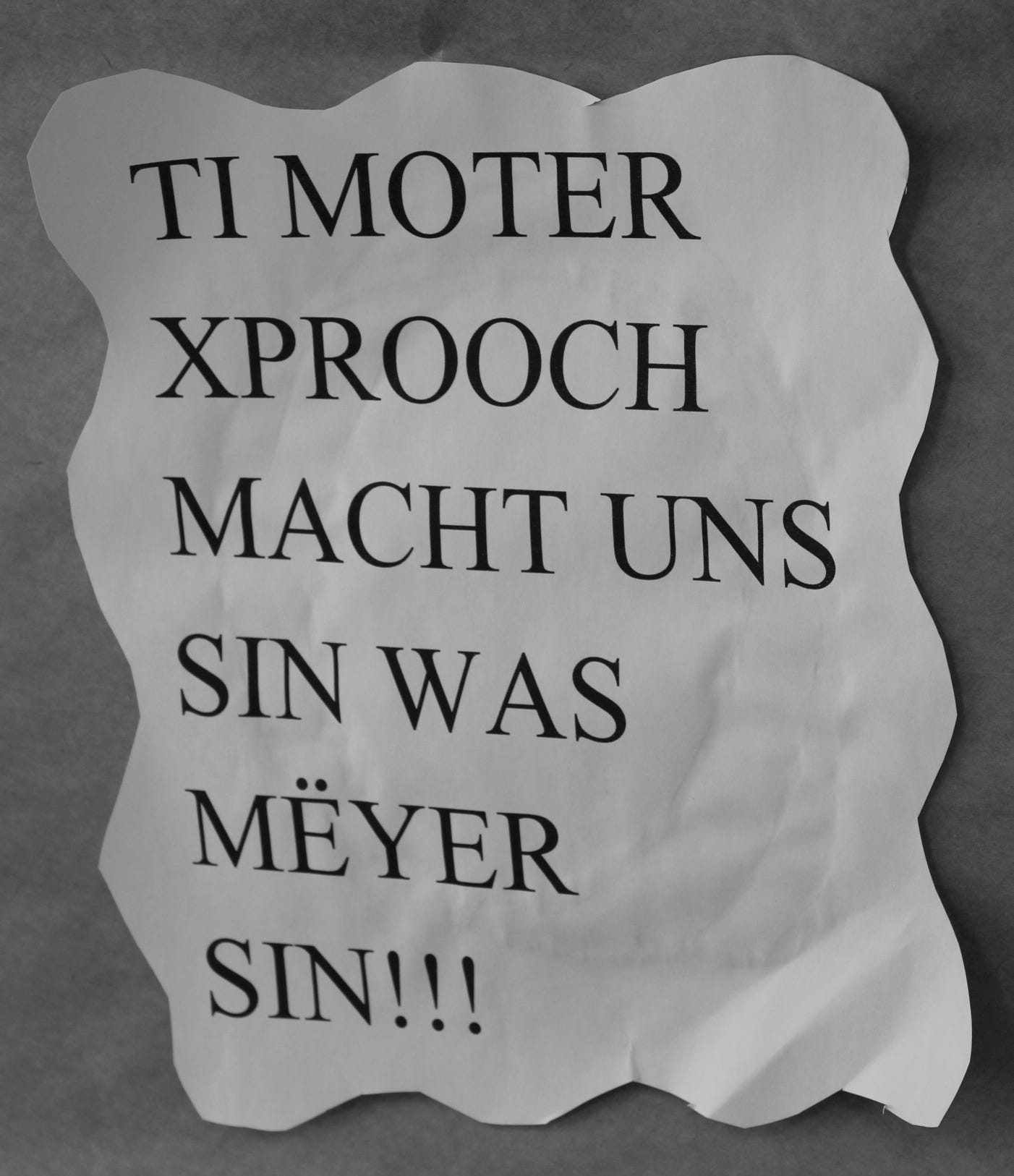

Although German has largely disappeared from the larger cities, in the small villages around Novo Hamburgo it has survived the world wars, the introduction of radio and television and a comprehensive Brazilian school system. To get to the capital of the Hunsrück region, you have to drive further north from Novo Hamburgo. If you think away the palm trees, the area between Reitersberg and Teewald could also be a German forest. The latter place should actually be called Tannenwald, but the name was already taken. By Brazilian standards, it is also quite cool now. June is winter in Brazil and in the main settlement area of the German-Brazilians, temperatures can drop to five degrees at night. It's not just the temperature that is more German than Brazilian, but also the cuisine: “Tomorrow we're serving potato cakes,” says Solange Hamester Johann from “Projekt Hunsrück” in the “Museum of Germanic Architecture” in Teewald, which she created and which is called Santa Maria do Herval in Portuguese. Hamester Johann is the soul and leader of the project, whose main achievement is to have introduced the Hunsrück language into the curriculum of elementary schools around Teewald. With the help of German linguist Ursula Wiedemann, who lived in Teewald for five years, a special orthography was developed that builds on Portuguese pronunciation to write the dialect in such a way that children can learn it easily. It looks like this, for example: “Yeete Folek mus ti importans fon sayn moter xprooch wise” (Every person must know the importance of their mother tongue). This sentence hangs on the wall at the entrance to the Castelo Branco elementary school, one of the schools where Hunsrückisch is on the curriculum. In 2007, Hunsrückisch was even recognized by UNESCO as a separate language in Brazil, Code hrx. In July 2012, the regional parliament in Porto Alegre recognized the “Lingua Hunsrik” as a historical and cultural heritage of Rio Grande do Sul with Law 14.061. The MP João Fischer, one of the initiators of this law, has published a small bilingual brochure in which he presents Hunsrückisch:

“Es sin xon 185 yoer heyer tsayt tas ti eyerxte Xermanixe layt in Prasil kewanert khom sin ... un hon, aach mit heroismus, sayn muter xprooch pehal, tii woo pis hayt, in te kemaynte woo se kekrint hon, kexproch wert, un tii xproche hon sich tsimlich al am Hunsrick aankepast ..." (page 6 of the brochure).

Solange Hamester Johann is proud of the schools and their primary school pupils who still speak the old dialect. “We see every day that it was right to chose this path, the children simply learn it more easily.” However, the language level of the children varies greatly. You can tell who still speaks Hunsrückisch at home with their parents or grandparents and who only learns it two hours a week as a “foreign language”. The children have difficulties with High German, Hamester Johann translates my German into Hunsrück.

After school, we drive through the villages with her, stopping here and there. We meet a German family in a house that is over a hundred years old and looks almost too kitschy to be real. We make a little small talk in Hunsrück German, go behind the house and admire the small lake where the owner likes to fish. Further on, back down the road to Teewald, we stop at the local corner store, where only the older people still speak fluent Hunsrück German. “There's just everything here,” Solange exaggerates wildly in front of half-empty shelves. We have to hurry a little to get our hands on the potato cakes in Teewald's trendiest restaurant. Here and there you can hear Hunsrück German, and sometimes a few sentences of High German, because some of the German-Brazilians were either visiting, working or studying in Germany and are happy to be able to talk about it in the language of their “old” homeland.

Strengthened by potatoes of various kinds, we meet Rodrigo Fritzen, the mayor of Teewald and his deputy, who is responsible for organizing the local potato festival. Teewald advertises itself as the “capital of the potato”. Fritzen speaks fluent Hunsrückisch and says that he uses it regularly both in the election campaign and in office, in personal conversations as well as in public speeches: “It goes down very well, people are happy to be addressed in their native language. I try to use it as often as I can,” says Fritzen over a sip of mate. “Actually, I shouldn't drink so much mate, but to celebrate the day, I make an exception.” The German-Brazilians, like the other southern Brazilians, are called “gaúchos” (pronounced ga-u-shos) just like the Argentinians and drink liters of mate just like them. In addition to organizing the potato festival, Fritzen is also working on expanding the infrastructure. There is still a problem with the water supply because “some farms are so remote that they are not connected to the water network. They only get their water from wells.”

Our first and last stop in Teewald is the “Museum of Germanic Archi-tecture”, Solange's refuge. On the tables are publications that Solange and her group have produced in Hunsrück, such as the introductory brochure “Mayn Eyerste 100 Hunsrik Werter.” The book is aimed at children and explains the first words with the help of pictures. These include, for example, “Ti Unerhos, tas Meetche, tas Himt, te Tix, Ti Panan, Tas Aay, tas Peen, ti Tseye, ti Sayf or ti Paat Xisel.” In the appendix there is help for teachers regarding pronunciation, spelling and translations. The latest project, a translation of Saint-Exupéry's “Little Prince”, is already available as a simple black and white copy and will soon be published as a booklet. The name of the museum is explained on the ground floor, where numerous models of German houses are on display, not only from Teewald, but also from other villages in the region: former German schools and institutions that also had German names before the world wars. On the computer on the upper floor, Solange has saved her radio show, in which she broadcasts news from the region in Hunsrückisch every week. Hunsrückisch is broadcast on several regional stations in different federal states.

Despite these developments, Felipe Kuhn Braun believes that the number of German speakers in the region will continue to decline. The preservation of the language depends very much on how local leaders behave. Some mayors promote German or Hunsrückisch at events and in schools, others do not. It hardly matters whether the person is of German origin themselves. “The former mayor of Dois Irmãos was German and stopped all activities to preserve the language. The current mayor is an Afro-Brazilian who fully supports these activities.”

Of course, one of the most important topics of conversation in Teewald, with the mayor in Novo Hamburgo and the Pickbrenner family in early June before the start of the World Cup was the World Cup. In High German, Margot Pickbrenner says that “of course we support our beautiful Brazil, no question about it.” When asked who should win, the schoolchildren in Teewald forget that they should actually be answering in Hunsrückisch and chant “Brasil, Brasil.” That was before 8 July 2014.